Abuja – 04 May 2021- When health teams discovered pockets of vaccine-derived poliovirus outbreaks in seven states in Nigeria (Lagos, Delta, Bayelsa, Zamfara, Niger, Sokoto and Kebbi), national and state authorities in collaboration with the World Health Organization (WHO) and partners quickly moved to quell the threat to the health of thousands of children.

In Lagos, Delta, Bayelsa, Zamfara and Niger, the cases were detected during the second half of 2020, while the remaining States reported cases in the first quarter of 2021.

In Lagos, the outbreak occurred in Makoko area, a network of landed and floating shanty communities on the Lagos Lagoon. Makoko houses more than 85,000 people and many are at risk of exposure to infections due to largely poor sanitation.

The swiftness of the outbreak response was to prevent an accelerated spread of the virus, a scenario that would set Nigeria’s progress back a few years. In August 2020, after a long period of battling the polio virus, Africa was declared free of the wild poliovirus by the independent Africa Regional Certification Commission.

Authorities are determined to keep the virus out of Nigeria’s borders. However, from time to time, vaccine-derived polio outbreaks occur in different parts of the country but are quickly addressed by health teams who are always on alert. There were only eight cVDPV2 cases reported from AFP in 2020 and 18 cVDPV2 cases reported in 2019.

The vaccine-derived virus, like the wild poliovirus, is a paralysing strain of the poliovirus that has mutated in low immunity settings affecting children who are not or under-immunized. Vaccines prevent children from infections and stop the virus from spreading.

Technical Contacts:

Dr Samuel Bawa; Email: bawas [at] who.int (bawas[at]who[dot]int); Tel: +234 810 221 0195

The first outbreak response was implemented in October 2020 some weeks after environmental samples containing traces of circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus type two (cVDPV2) were detected by the surveillance team supported by WHO in the Lagos Mainland area.

In Bayelsa, the state team received a positive result of cVDPV2 in late January 2021, from a stool specimen of a 1-year old female child with acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) who resides in Ekeremor LGA that shares riverine borders with Delta state.

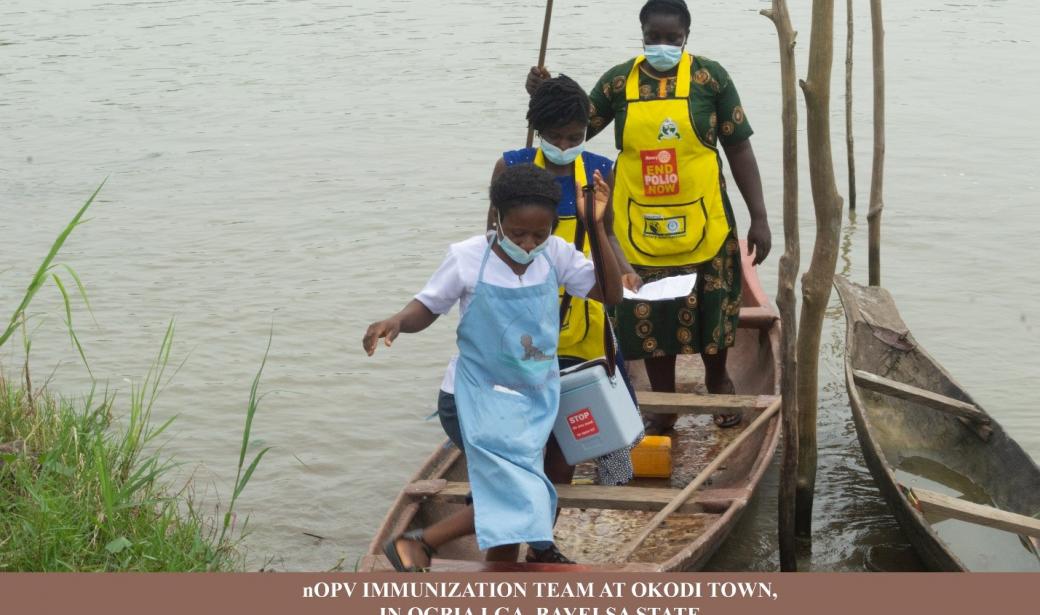

The case was genetically linked to a previous case of a 9-month-old boy from Delta state reported in August 2020. Just like Makoko, the vaccination team at Okodi town in Ogbia LGA, in Bayelsa have to cross the river using a canoe to get to the houses located within the riverine areas.

In Bayelsa, community elders and health workers, supported by WHO, have been sensitizing parents and families since August 2020 on the need to be cooperative with vaccine-teams once they arrive. That advocacy helped smoothen the path and made it faster to vaccinate the children in October during the first round of the campaign and again in December.

There are a few challenges with reaching all children in this community. The population in many of riverine areas is largely under-educated and myths and rumours surrounding vaccines are rife. Some rumours have it that vaccines can lead to infertility in children, while others say vaccines spread diseases, including COVID-19. Allaying these rumors is part of the communication and demand creation approach during the campaigns.

However, experts say there is little chance of a reemergence, as Nigeria’s polio surveillance system has grown in strength over the years, comprising a range of experts, community workers and local leaders working together to achieve positive results and supported significantly by WHO. It is this surveillance system that helped the country defeat wild polio in 2020 and it is the same system that has been adapted to fight the COVID-19 disease which emerged in the country in March 2020. For example, COVID-19 responders are using active case search strategies, a method that was employed to fight polio by engaging local volunteers to search for cases of Acute Flaccid Paralysis (AFP) which is a clinical symptom of poliomyelitis.

Back in Lagos, a local government facilitator, Catherine Anyadiegwu, double-checks a house marking to ensure it is properly cleared.

Communications Officer

WHO Nigeria

Email: hammanyerok [at] who.int (hammanyerok[at]who[dot]int)